On the Bold Leadership of Black Expat-Explorers

“We shall not cease from exploration, and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time.” ~ T.S. Eliot

Insightful words by one of the world’s foremost social critics and poets, American-born T.S. Eliot (1888 - 1965) as he travelled to England in 1914. He later renounced his American citizenship and became a British subject. Eliot was a white American born to a prominent Boston family. The expat-explorers who are today’s focus did not share these characteristics. Yet they all undertook a similar exploration, which changed their lives forever.

A rarely discussed part of the African American experience is the African Americans who ventured beyond America’s borders. Many African Americans left the United States and took up residence in other countries; some for extended stays, others permanently.

Between 1916 and 1930, over a million African Americans moved to the northern United States.

They were not part of the major migrations in African American history. Recall that there was the First Great Migration (1916 – 1930) when African Americans moved from the rural South to the industrial North followed by the Second Great Migration (1940 - 1970) when African Americans moved to the western states, particularly California for the shipyard industry.

Yet the current period of Black expatriation can be considered a radical Migration or exploration, led by courageous and bold Black explorers.

Many formerly enslaved Black people left the United States. One notable “explorer” was abolitionist and orator, Frederick Douglass (c. 1818 – 1895). Encouraged by white American friends who feared that Douglass’s “fugitive” status threatened his safety and freedom, Frederick Douglass traveled to Great Britain and Ireland where he continued with his abolitionist activities. Travelling to Ireland and Britain was transformative for Douglass who remained for nearly two years. He noted with astonishment,

“Instead of a democratic government, I am under a monarchical government. Instead of the bright, blue sky of America, I am covered with the soft, grey fog of the Emerald Isle [Ireland]. I breathe, and lo! the chattel [slave] becomes a man. I gaze around in vain for one who will question my equal humanity, claim me as his slave, or offer me an insult. I employ a cab—I am seated beside white people—I reach the hotel—I enter the same door—I am shown into the same parlour—I dine at the same table—and no one is offended ... I find myself regarded and treated at every turn with the kindness and deference paid to white people.” ~ Frederick Douglass

Others had similar illuminative moments. Although many African Americans left the United States for different reasons than Douglass, the experiences and sentiments were similar. Following the slavery and Reconstruction eras, many prominent African Americans left the United States, frustrated with racism and the deeply oppressive society that denied their basic civil rights and liberties. They chose to explore another way of living and expressing themselves that was routinely denied them at home.

Civil rights activist and dancer, Josephine Baker (1906 – 1975) was a notable African American who deeply felt the oppression and lack of opportunities at home. She makes a candid comparison between her life as a Black American in the United States and her life in France.

“I have walked into the palaces of kings and queens and into the houses of presidents. And much more. But I could not walk into a hotel in America and get a cup of coffee, and that made me mad.” ~ Josephine Baker

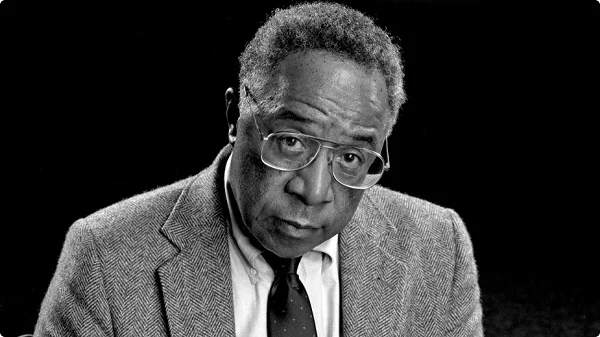

Paul Robeson in Russia. In the United States, Robeson fought racism, lynching and McCarthyism.

Lawyer, actor, and social activist, Paul Robeson (1898 – 1976) made the same observation and had a similar experience.

“In Russia I felt for the first time like a full human being. No color prejudice like in Mississippi, no color prejudice like in Washington. It was the first time I felt like a human being.” ~ Paul Robeson

Yet they made different expat-life choices: Paul Robeson returned to the United States. Josephine Baker did not. Yet both continued to their activist work fighting prejudice and promoting peace and equality in the United States and around the world.

One false belief is that all Black expats left because of racism and subsequently found equality in Europe. Aviator Bessie Coleman (1892 – 1926) left the United States because she sought to earn her pilot’s license. This wasn’t possible in the United States because of racism and sexism, which didn’t allow a Black woman to attend flight school. She iconically proclaimed,

“I refused to take no for an answer.” ~ Bessie Coleman

She learned French and, in 1920, moved to Paris. Became the first woman of African American descent to earn an aviation license and the first African American to earn the international aviation license. This would not have been possible had she remained in the United States. Yet following her flight studies and training, she returned to the United States to much acclaim and fame. But her experiences living in both countries led her reflect,

“The air is the only place free from prejudices.” ~ Bessie Coleman

African American expat-explorers have had a variety of life experiences.

Following publication of his autobiographical novel, Black Boy (1945), the French Government actually invited novelist Richard Wright (1908 – 1960) to visit France. Wright immediately fell in love with Paris, writing in a postcard, “I’ve never felt a moment of sorrow,” and, comparing it with New York City, wrote that there is “no terrifying bigness” in Paris.

Wright remained in Paris and eventually disconnected himself from the Communist Party with whom he had developed a close affiliation. Although his literary output declined—though he published Uncle Tom’s Children (1938) at this time—he had a massive impact on the literary community in the United States. Many in the African American community felt animosity towards Wright, claiming that he had abandoned his responsibilities at home. Still, as the Oxford Companion to African American Literature has pointed out, “Richard Wright changed the landscape of possibility for African American writers.” Richard Wright remained in Paris until his death in 1960.

Author and social activist, James Baldwin (1924 – 1987) had a similar experience. Although critical of Richard Wright after the publication of Native Son (1940), accusing Wright of distorting artistic truth into protest and propaganda, James Baldwin also expatriated to France for the first time in 1948, following a racist incident at a segregated restaurant. Baldwin was determined to distance himself from American prejudice but was also equally determined to grow as a writer outside of a prescribed African American context. He settled in Paris and published in many literary anthologies while becoming involved in the cultural radicalism movement of Paris’s Left Bank. . However, Baldwin returned to America to participate in the civil rights movement, which rejected him because of his homosexuality. In 1970, Baldwin returned to France. He learned to speak French fluently and entertained political and artistic glitterati from his home in the south of France. James Baldwin remained in France until his death in 1987.

Baldwin, like many before and after him, had similar sentiments and discoveries as an expat-explorer when he said,

“I met a lot of people in Europe. I even found myself.” ~ James Baldwin

Now consider this….

Stephen Bishop was the first person to explore the Mammoth Caves (below), which he described as “grand, gloomy and peculiar.”

African Americans have been avid explorers. From reaching the Polar Regions, exploring caves, scaling mountains and even venturing into space, African Americans have had a solid presence forging into new territory, asserting a new mindset and making the world more accessible to all of us.

Stephen Bishop (c. 1821 – 1856), an enslaved Black man, who was the first guide and explorer at the Mammoth Caves. Bishop was the first to explore beyond the Bottomless Pit, describing the massive cave system as “grand, gloomy and peculiar.”

Sophia Danenberg (b. 1972) who has scaled 19 peaks. In 2006, Danenberg climbed Mount Everest after one week of preparation, while suffering from bronchitis, frostbite and a clogged oxygen mask. About climbing Mount Everest, she responds, “I didn’t train to climb Everest. I was already training constantly.”

Matthew Henson (1866 – 1955) reached the North Pole in 1909. He learned the Inuit language, Arctic survival techniques, polar and sea navigation and dogsledding. On reaching the North Pole, Henson exclaimed, “I’m the first person to sit on top of the world!”

Barbara Hillary (b. 1931) who was the first Black woman to reach the North and South Poles. She reached the North Pole at age 75 and the South Pole at age 79. She is also a lung and breast cancer survivor. Ms. Hillary is no ordinary retiree, she says, “I prefer to set my own course as much as I can on the map of life.”

There are so many other African American expat-explorers who cannot be found in the traditional history or adventure books.