On Black Literary Explorers

“We must go beyond textbooks, go out into the bypaths and untrodden depths of the wilderness and travel and explore and tell the world the glories of our journey.”

~ John Hope Franklin (1915 – 2009)

Scholar and historian John Hope Franklin’s elegant description the work and world of the literary-explorer takes reader into a “wilderness” of new experiences and old experiences lived for the first time. The focus is on the journey and the destination as the literary-explorer examines and analyzes the experiences encountered.

Exploration is evolving to adopt new meaning and significance. In the past, exploration focused on scaling mountains, trekking across vast deserts, sailing to far away places, searching through underground cave systems or other “adventurous” activities. But exploration today goes far beyond these activities as illustrated by the literary-explorer who takes the reader into a realm presented by the writer and experienced by the reader.

Exploration is in our nature. We began as wanderers, and we are wanderers still. ~ Cosmologist Carl Sagan (1934 – 1996)

And our wandering literary-explorers have produced some of the most profound exploratory works in modern American literature.

In his groundbreaking memoir, Black Boy (1945), novelist Richard Wright (1908 – 1960) explores the life of a Black boy growing up in the rural south then moving to Chicago. This literary-exploration takes the reader through the difficulties of growing up Black in the American south then seeking the hope—like many African Americans as they left the deeply oppressive South—of freedom, liberty and respect in the northern United States. What he discovered fell short of the dream promised.

Novelist and essayist, Ralph Ellison (1913 – 1994) was another literary-explorer who eloquently explored the heart and mind of an African American man living a “secret” existence in his revealing novel, The Invisible Man. The novel opens with the reflections of the invisible man,

“I am an invisible man. No, I am not a spook like those who haunted Edgar Allen Poe; nor am I one of your Hollywood-movie ectoplasms. I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fiber and liquieds—and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me.” ~ Ralph Ellison, The Invisible Man (1952)

Ralph Ellison’s The Invisible Man

Exploring the depths of the African American experience, Ellison and Wright produced thought-provoking novels that put the Black life and thought on paper, for all to read and reflect upon. Although The Invisible Man and Black Boy were both fictional works, they also contained distinctly nonfictional elements. These novels were precursors to the nonfiction novel as a genre utilizing fictional characters and scenes as well as undeniably factual experiences and emotions. Yet the terrifying novel, In Cold Blood (1966) by Truman Capote (1924 – 1984) is credited with this literary development.

A white man turned black in John Howard Griffin’s Black Like Me. Many viewed Griffin as a hero for his seminal work. Others felt betrayal.

A different exploratory work, that appeared initially to blur the line between fact and fiction, is John Howard Griffin’s (1920 – 1980) investigative work, Black Like Me (1961), which took its name from the last line of Langston Hughes’ (1901 - 1967) yearning-for-freedom poem, Dream Variations (1926). In Black Like Me, the main character is a white man (John Griffin himself!) who undergoes treatments to turn his skin from white to black. Then he ventures for six weeks into the segregated states of Louisiana, Arkansas, Mississippi, Alabama and Georgia to explore the life of a Black man, keeping a copious daily journal of his experiences with both whites and blacks. His journal was both shocking and revealing as he exposed the basic difficulties of life for Black people (he couldn’t find a toilet to use because most are for whites only), annoying experiences (he was politely told to leave a “whites only” park, and frightening experiences in which he was threatened with imprisonment. Following release of the book, Griffin became a celebrity for a short time and many whites appreciated his book because his exploration helped them to understand the Black experience in America. Others, however, felt betrayed and responded with hostility and threats.

October 28, 1959

“For years the idea had haunted me, and that night it returned more insistently than ever.

If a white man became a Negro in the Deep South, what adjustments would he have to make? What is it like to experience discrimination based on skin color, something over which one has no control?”

~ John Howard Griffin, Black Like Me (1961)

Turning back in time, another fearless literary-explorer, Novel Prize-winning author, novelist and Professor Emeritus, Toni Morrison (b. 1931), explores and shows the horrors of slavery in her emotionally charged novel, Beloved (1987). Following a single family from 1873, slavery continues to haunt the members, literally in the form of a ghost who makes sporadic but powerful appearances. In Beloved, Toni Morrison explores many important—but rarely discussed—effects of slavery such as the psychological impact of slavery, its impact on families and relationships, the painful memories of slavery and the genocidal effects of slavery. For exploring and relating these topics, Toni Morrison was widely criticized as overly sentimental, even angry. Yet this exploration into the horrors of slavery (with comparisons to the Jewish Holocaust) and the short- and long-term effects of slavery brought an important piece of history to life that many people want to forget or diminish.

Also based primarily during slavery in America but including Africa and the trans-Atlantic slave trade, Alex Haley’s iconic and lineage-based based novel, Roots: The Saga of an American Family (1976), was another look into America’s unhappy history. Alex Haley (1921 – 1992) reportedly researched his ancestors’ history from the capture of 17-year old Mandinka boy, Kunta Kinte, in Gambia through the middle passage across the Atlantic and his eventual enslavement in the United States. The book is accurate described as “The saga of an American family” as it follows seven generations of Kunta Kinte’s family during slavery and beyond. Although Alex Haley acknowledged that the book is a work of fiction in describing the dialogue and incidents of the family, Haley also confirmed that the actual people (and their names) and their life stories are based on extensive genealogical research in the United States and Gambia. The impact of Roots was immediate and pervasive by presenting a “different” story of an “American family” of which most Americans (both white and black) were unfamiliar. His literary- and lineage-based exploration led others to take the same path, particularly Black Americans, and caused the field of genealogy to soar.

A uniquely creative form of literary exploration is the time travelling narrative, Kindred, (1979) by novelist and essayist, Octavia E. Butler (1947 - 2006). In her “groundbreaking masterpiece,” Dana, a modern Black woman in her mid-twenties, is suddenly snatched from her California home and transported back in time to the antebellum south where she is asked to save the life of a drowning white boy. Dana does return from this time-transporting voyage back to her modern life—just to be constantly returned to south during slavery. Dana’s visits to the difficult period grow longer and increasingly dangerous. Kindred is an interesting work of science fiction that frighteningly merges the slave period with modern times. Strictly fictionalized—Butler avoids the blurring of fact and fiction—the story or more accurately, the narrative explores the experience of slavery from the perspective of a modern woman. Butler shows her courage and creativity as a literary-explorer, presenting the reader with a hybrid memoir and fantasy novel expanding the genre of the “neo-slave” narrative. (“Neo-slave narratives are fictionalized autobiographies of enslaved Americans.) Written from the first-person perspective, Kindredand other “neo-slave” narratives explore a new genre but more importantly transport modern readers into the life of Americans who were enslaved. This modern touch, expertly written by Octavia E. Butler, makes the experience more real and reachable. In Dana’s first time-travel experience, she says,

“I turned, startled and found myself looking down the barrel of the longest rifle that I have ever seen. I heard a metallic click, and I froze, thinking I was going to be shot for saving the boy’s life. I was going to die.

…

Then the man, the woman, the boy, the gun all vanished.

I was kneeling in the living room of my own house again several feet from where I had fallen minutes before. I was back home—wet and muddy but intact.”

~ Octavia E. Butler, Kindred (1979)

This is not the last time that Dana will face death. Octavia E. Butler inventively explores and invites the reader to explore the issues of race, sex, power and humanity through Dana and the individuals that Dana encounters on both sides of her time travels.

Blurring the line between fact and fiction, real and imaginary, and comfort and growth is the legacy of the literary-explorer as noted by the WWI-veteran, Richard Aldington (1892 - 1962) writing of his experience on the western front in Death of a Hero (1929),

“Adventure is allowing the unexpected to happen to you. Exploration is experiencing what you have not experienced before.”

~ Richard Aldington, Death of a Hero (1929)

Now consider this…

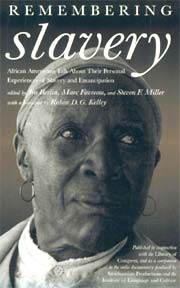

Before the “neo-slave narrative” came the “ex-slave” narratives, which were actual first-hand recollections of life as a slave in the United States. Some were funded by the Federal Writers’ Project that preserved many slave narratives in written form and audio recordings as in the book, Remembering Slavery (1996), which is described as “a short story with a long history.” Audio recordings are some of the most captivating of all the narratives in the Remembering Slaverystories. Ex-slave narratives are as diverse as any work of fiction with one notable exception: the stories are true. Some are eloquently written such as the most famous narrative written by Frederick Douglass (c. 1818 – 1895) such as Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845).

Another narrative rivaling the rhetoric and literary skills of Frederick Douglass was Harriett Jacobs’s (1813 – 1897) evocative Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Written by Herself (1861). Harriet (renamed Linda in the book) changes the name of the real-life characters to protect herself as a fugitive slave. Her book is considered is a critical change from previous African American historiographies and is a forerunner to the radical feminist literature. Incidents focuses on gender issues, including sexual abuse, reproductive violence and the race-gender dichotomy. Preservation of these narratives is an essential part of American history and honoring the Americans who were enslaved for hundreds of years.

by Robin Lofton