On the Power of Slave Narrative

“Ten years I toiled for that man without reward. Ten years of my incessant labor has contributed to increase the bulk of his possessions. Ten years I was compelled to address him with downcast eyes and uncovered head—in the attitude and language of a slave. I am indebted to him for nothing, save undeserved abuse and stripes.”

~ Solomon Northrup (1807 – unknown), Twelve Years a Slave

Eloquently describing his life after he was kidnapped and sold into slavery, Solomon Northrup, in Twelve Years a Slave (1853), transformed the unknown world behind the “Cotton Curtain” into a vicarious experience for his white readers. His narrative and many others helped to challenge and ultimately bring an end to the “peculiar institution” of slavery in America.

Narratives are powerful. And the narratives of the enslaved Africans in America are some of the most powerful and moving accounts ever written. Their descriptions of the oppressive and de-humanizing machinery of slavery can never be forgotten.

Julius Lester’s To Be a Slave (1998) is a disturbing collection of personal narratives from former enslaved persons; Julius Lester (1939 - 2018) opens with a powerful description,

“To be a slave. To be owned as another person, as a car, house, or table is owned. To live as a piece of property—a child sold from its mother, a wife from her husband. To be considered not human, but a “thing” that plowed the fields, cut the woods, cooked the food, nurse another’s child; a “thing” whose sole function was determined by the one who owned you.” ~ Julius Lester, To Be a Slave

With more detail, he describes how enslaved people were treated behind the “Cotton Curtain.”

No level of humanity was allowed the “slave.”

“They whipped my father ‘cause he looked at a slave they had just killed and cried.” ~ Julius Lester, To Be a Slave

No personal identity was allowed the “slave.”

“Without a name of his own, the slave’s ability to see himself apart of his owner was lessened. He was never asked who he was. He was asked, “Who’s nigger are you?” The slave had no separate identity. He was always Mr. So-and-so’s nigger.” ~ Julius Lester, To Be a Slave

No family life was allowed the “slave.”

“Never knew who massa done sold. I remember one morning a white man rode up in a buggy and stop by a gal name Lucy that was working in the yard. He say, “Come on. Get in this buggy. I bought you this morning.” Then she beg him to let her go tell her baby and husband goodbye, but he say, “Naw! Get in this buggy! Ain’t got no time for crying and carrying on.” ~ Nancy Williams, The Negro in Virginia (1994)

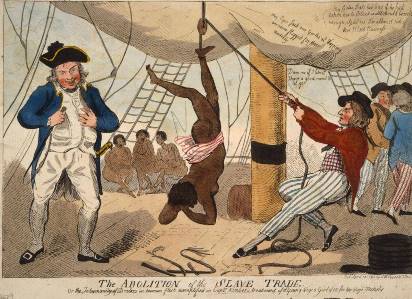

Slave narratives continue as an important literary tool. They offer both a glimpse into the life of an enslaved person as well as a view of the white supremacist power structure that kept Black men and women enslaved. The narrators served as witnesses to the pain and struggle of slaves in the antebellum south of America, but they also bore witness to the aspirations, feelings, and victories of the Black American slave. In short, the slave narrators humanized the “slaves.” Using this genre—developed through vivid storytelling—the slave narrators ignited a movement towards abolition and freedom.

While most slave narrators shared one common (and obvious!) status, they had vastly different experiences. In the Harriet Jacobs’, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861), she chronicles her life as a biracial slave in North Carolina. While noting many happy times in her childhood, she painfully describes her life in sexual bondage to her master who asserted unyielding power over her and her (their) children.

Harriet Jacobs (1813 – 1897) wrote this narrative to enlighten white women of the powerlessness endured Black slave women under the white patriarchal system of slavery. This early feminist narrative attempted--through story telling--to establish a connection between white and black women in the antebellum south. It did not happen. Even the famed abolitionist Harriett Beecher Stowe (author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin) refused to endorse Harriet Jacobs’s narrative, which defeated its distribution for many years.

“Women are considered of no value, unless they continually increase their owner's stock. They are put on a par with animals. This same master shot a woman through the head, who had run away and been brought back to him. No one called him to account for it. If a slave resisted being whipped, the bloodhounds were unpacked, and set upon him, to tear his flesh from his bones. The master who did these things was highly educated, and styled a perfect gentleman. He also boasted the name and standing of a Christian, though Satan never had a truer follower. ~ Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861)

In contrast to Harriet Jacobs’s Incidents(italics), Frederick Douglass’s narrations focused on the terrible life of the slave boy-turned-man. Frederick Douglass (1818 – 1895) discusses his never-ending urge for education and freedom. While he never experienced sexual violence like Harriet Jacobs—and many other female and male slaves—Douglass lived with constant violence and threat of violence and death because of his desire for learning and dominant physical and mental strength. In his narrative, Douglass states,

“I have observed this in my experience of slavery, - that whenever my condition was improved, instead of its increasing my contentment, it only increased my desire to be free, and set me to thinking of plans to gain my freedom. I have found that, to make a contented slave, it is necessary to make a thoughtless one. It is necessary to darken his moral and mental vision, and, as far as possible, to annihilate the power of reason. He must be able to detect no inconsistencies in slavery; he must be made to feel that slavery is right; and he can be brought to that only when he ceased to be a man.”

― Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass(1845)

As a literary form, the slave narratives of the 18th and 19th centuries, changed people and the country. Southern slave owners had kept the horrors of the oppressive slave system locked away from “genteel” society and northern city dwellers. But slave narratives aired the dirty laundry of the brutal system that was enslaving and oppressing countless Black Americans. Moreover, slave narratives showed Black people as intelligent, sophisticated and courageous—as a people deserving of the rights and freedoms proclaimed in the country’s Constitution and even Declaration of Independence.

Harriet Tubman led hundreds of enslaved men, women, children to freedom.

Nestled among the themes of brutality, dehumanization and cruelty lay other surprising and uplifting themes: Courage and responsibility. In many antebellum narratives, the attainment of freedom is signaled not simply by reaching the free states, but by renaming oneself and dedicating one's future to antislavery activism. Frederick Douglass, Solomon Northrup, William Wells Brown, Harriet Jacobs, Booker T. Washington and many others wrote about their life and escape from slavery. But they never forgot the “ones left behind.” At great risk, they worked tirelessly for the abolition of slavery and to help other enslaved people to escape to freedom.

Narratives were and remain a literary tool for introducing others into one’s personal life experience. Enslaved people bravely and shamelessly shared their personal stories of brutality, fear and inventiveness throughout a life in which they were considered only as personal property. Yet their stories appealed to the unexpected humanity of people who rejected the indecent power of owning the body and soul of another human being. And their stories changed a country forever.

Consider this…

Some notable “slave” narratives were not written by former slaves. Harriett Beecher Stowe’s revolutionary novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), opened the “cotton curtain” and exposed the ugliness of slavery. Another radical novel, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884) by Mark Twain (1835 – 1910), explored slavery, racism and identity from the perspective of a young white boy. Despite intense criticism, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn is considered the first “Great American Novel.” The legacy of Harriett Beecher Stowe (1811 – 1896) is also secure. When President Abraham Lincoln (1809 – 1865) met the modest writer, he exclaimed about Uncle Tom’s Cabin, “So this is the little woman who wrote the book that started this Great War!” Both books are seminal works on the conflicts and prejudices of American society in the antebellum South.

*************************